Connor Sparrowhawk’s death on 4th July 2013 was entirely preventable.

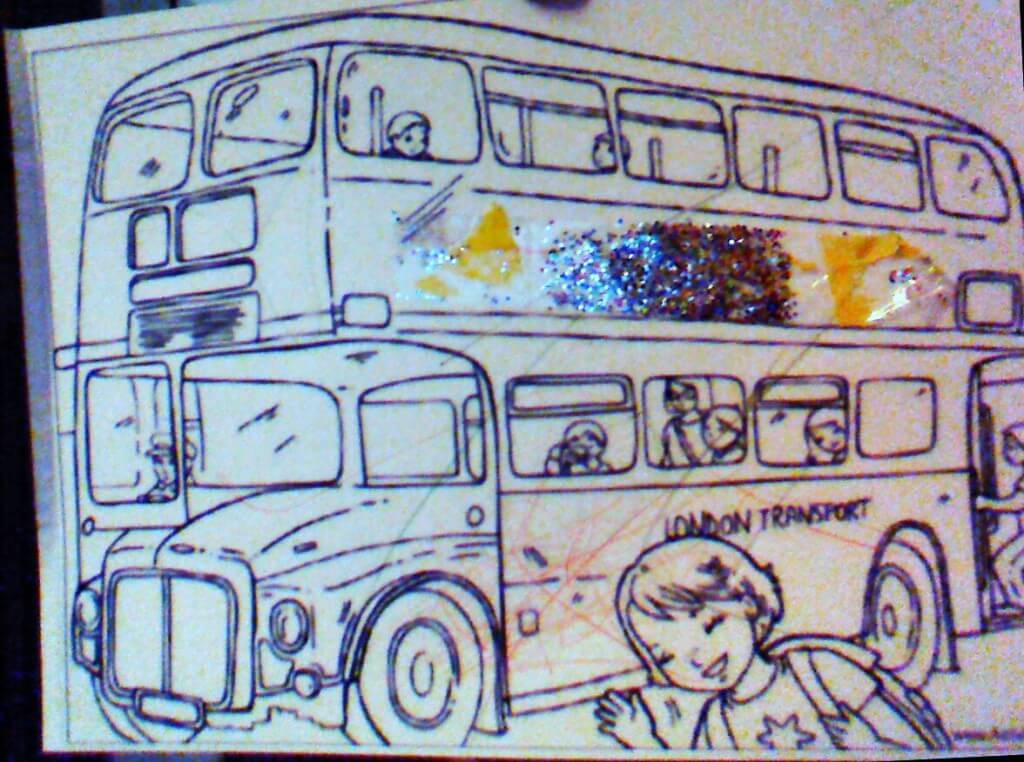

He was just 18 years old, a fit and healthy young dude known online and by his loved ones as Laughing Boy (LB), LB loved buses, London and Eddie Stobart, he also happened to have autism and epilepsy.

LB drowned in the bath at an Assessment and Treatment Unit where he had been for 107 days. How can it be that in a fully staffed assessment and treatment unit a young man with a known history of seizures can drown in a bath with nobody noticing until it was too late?

His mother Sara’s fight to bring about #JusticeforLB started with a battle to get an independent investigation into his death commissioned, and another fight for its publication. The #107days campaign is borne out of her wish to inspire, collate and share positive actions being taken to bring about #justiceforLB and all other young dudes. You can read more of the background here and here.

I started to follow Sara’s blog way back when she was talking about what a good life would look like for Connor; a fellow social researcher unpacking the big issues around disability; how heartbreaking to read of his death in July 2013, I felt as though I knew LB and his family, knew the direction in which they were headed.

I asked to adopt day 48 of #107days because it’s my daughter’s birthday, I have a strong interest that she develops a desire to tackle issues of social (in)justice and so it seemed an appropriate way to focus my attention. This blog post is where my personal and work lives collide. I have spent much of my working life campaigning for the availability of independent advocacy in Gateshead at Gateshead Voluntary Organisation Council, but in doing so realised early on that my job was not just to promote services and seek funding, but to challenge the practice that advocates see in their day to day work.

Something from my first ever self-advocacy workshop has always stuck in my mind, I delivered a session with a group of young adults with learning disabilities, we looked at some images associated with advocacy, one guy piped up “why do they always use a photo of a megaphone in these speaking up things? You can shout loud and clear but they still don’t hear you, it should be a picture of a fella and his advocate with the hundred-odd letters and emails they’ve sent about a problem instead…”

I want to use the opportunity to blog on day 48 about the importance of having a voice and being heard. Why is it so significant to know that Connor loved Eddie Stobart, buses and speaking his mind? It brings a context that we all have our own interests and our own ideas about what a good life is like, knowing about people also makes them visible and difficult to ignore.

Sara’s blog posts and responses to the independent investigation into Connor’s death make one thing so obvious – I can practically hear her shouting loud and clear about his epilepsy, seizures, about her rights, LB’s rights – here was a voice that was not being heard.

So if health and care services don’t hear the voices that are shouting loudly what about the people who have no family, no advocate, no-one speaking for them? The Department of Health’s Winterbourne View report, noted: “Failure to listen to people…and their families [is] a common experience and totally unacceptable”. So a voice is speaking, but what are the barriers to being heard then?

Connor went from being at home with his family to being on an assessment and treatment unit. Let’s take a moment to think about what a home environment might be like, familiar, comforting and for LB somewhere where he and his family would have spent years navigating what a good life looked like, he shared a room with his brother his whole life, creating an environment where he could be expressive and learn to speak his mind.

Imagine being 18 years old and moving into a hospital environment, to live, for 107 days (or, sadly, possibly longer)?

LB was admitted under the Mental Capacity Act, later he was detained under the Mental Health Act. The independent investigation highlighted that staff on the unit tried to explain his rights but LB became distressed so they stopped. The independent investigation suggests there was a lack of clarity from staff both about the purpose of the unit and about why LB was there; if staff did not have a clear understanding of why LB was there how on earth could LB have understood? Shouldn’t he have been helped to understand?

When someone with a disability or mental health issues known to social services turns 18 they undergo a social care process called transition. In effect they transition from children’s to adult services. Who could ensure that LB did understand? His mother surely?

She had to navigate a confused and confusing access system owing to the fact that Connor was over 18 and therefore an adult and could choose or refuse to see his family (dependent, we might assume, on how well or otherwise staff communicated with him?) There is a strong sense from Sara that she wanted LB to live an independent life and make his own decisions, but under these circumstances it seems once the age of transition is reached common sense goes out of the window and regulations about access become king. How come for the first few weeks access was largely unrestricted? Was there some sort of unspoken settling in period after which families are somehow no longer needed?

A final word on speaking up in care settings, I strongly believe that all vulnerable adults should have access to someone who can help them speak up or speak on their behalf, the Care Bill looks set to move in this direction, but how will it be paid for and how will it be delivered? People have had a right to an Independent Mental Health Advocate under the MHA for some years now and we know many don’t see this right respected because of patchy provision, poor commissioning or poor application of the law.

What do we do about making listening the norm against a backdrop of health and social care systems, treatment options, legislation, guidance and working practices? What stops it? Is it that in cases like this decisions must be made quickly so they are made on the person’s behalf? Maybe they’re felt to be in danger or they have an urgent and pressing health concern and the person and their family get left behind? Clearly the very fact that statutory advocacy exists at all suggests we understand the need to hear the person in all of this, so why did Connor’s mum have to fight to be heard?

What would make a difference?

LB’s situation was surely one of the most vulnerable, a young man away from home, navigating a complex system of physical and mental health, sometimes experiencing the conditions that seem to go alongside presenting challenging behaviours; medication, detainment, restraint, with very little support. The idea of whole person care is gaining momentum, moving from the silos of health, mental health and social care to ‘seeing the whole person’ – this must include the bigger picture of families and carers, seeing them and hearing them too.

Properly funded advocacy for all vulnerable adults would be a good starting point. The NHS Constitution is supposed to extend in law a right for patients and their families to be heard. This is not a document to be referred to only in case of complaint but to be woven into practice, especially at the harder end of care. We need to see it given teeth, with a robust evidence base to monitor its application, and it needs to hold the same importance for practitioners as clinical guidelines do.

My blog’s readership is in the main parents, so I wanted to take the time to make an ask. Take a look at this post on what you can do to support this campaign, maybe consider taking the time to talk to someone else about LB’s story, or do something Joss and I did together and draw a red bus, or my crafty readers might want to make a quilt square. Let’s keep the momentum going.